It’s a sin to live this well—Harvey Danger “Flagpole Sitta” (1997)

At the start of the New Millennium, cultural critic Ellen Willis compiled ten years of her essays into the book Don’t Think, Smile!: Notes on a Decade of Denial. As the title of her book indicated, these essays were all united by one main theme: that the nineties was a decade of poisoned optimism and everyone had drunk the Kool-Aid.

“Companies are shedding managers and replacing engineers with machines. The job markets in the academy and publishing industry are dismal, support for artists and writers even scarcer than usual, the public and non-profit sectors […] steadily shrinking. […] Wealth is still increasingly concentrated at the top and, last I looked, still handily outstrips other sources of power.”

Willis recognized and named all of these problems listed above, but she also recognized that Americans appeared incapable of change. Everyone had chosen instead to peep into strangers’ personal lives and entrench themselves in incoherent culture war positions that had been awkwardly reverse engineered to maintain a veneer of moral high-ground.

In a 1999 retrospective for Vanity Fair, David Kamp described the nineties as “The Tabloid Decade.” He was correct. The nineties was the decade that gave us Jerry Springer and the ascendance of the 24/7 news cycle. The nineties was the decade when the stylized melodrama of daytime soaps were supplanted by the real-life cinematic thrill of a Heisman Trophy Winner-turned Hertz spokesman-turned wife murderer speed on the Santa Ana Highway. In the Clinton years, the private conflicts of the Bobbits and Buttafuocos took airspace alongside conflicts “such as the L.A. riots, the Unabomber case, the Oklahoma City bombing, and the impeachment-eve blitz of Iraq.” Talk about context collapse. But then again, Jean Baudrillard did write, in 1995, that The Gulf War Did Not Take Place, given that the atrocities of post-Peak Oil imperialism are impossible to render real in the self-congratulatory media soundbites that had replaced news in the nineties.

Kamp closed his Vanity Fair essay by asking “as the Tabloid Decade draws, at least numerically, to a close, you can’t help but wonder what’s been lurking the whole time in that ignored parallel universe known as reality. You wonder if whatever’s lurking there […] is going to rear up and demand our penance for ignoring it.” We no longer need to wonder. Every day, in the 21st century, we pay our penance.

The Gulf War Did Not Take Place and This Playlist Is Not About Bill Clinton. Bill Clinton is mainly a name I use—again and again—as a synecdoche for the tenor of the nation during the majority of the nineties. With all that being said, the first song on this playlist is about Bill Clinton. Really, is there any other way to begin the playlist than by having Lou Bega declare “flirting to me is just like a sport” and then—out all the names to choose from—bragging about banging a girl named Monica?!

Monica, Gennifer, Paula, Juanita, Kathleen, Elizabeth, Sally, Dolly: Bill Clinton sure had a lot of women in his life, and all were presented to the public as a line-up of tabloid fodder freed from any pesky context. The allegations that followed Bill Clinton —that still follow Bill Clinton if we are being honest—work as a great example of the context collapse that his era of presidency saw solidified. Each woman had a different story that necessitated a different type of public response, but all events and accusations got lumped into a parade of media appearances. The accusations were refracted not by the content of the stories, but by how effectively the women could fulfill a brief niche media role.

In this context of no context, in this content starved endless news media ecosystem where Hugh Grant’s solicitation of a sex worker, and Pam and Tommy’s stolen sex tape, and Charles and Camilla’s private conversations, and the Srebrenica Massacre, and Mary Kay Letourneau’s obsession with a sixth-grade student, and Newt Gingrich halting the government, and a Bombing at the Atlanta Olympics, all got scrambled together on our personal TV screens, is it any surprise that by 1998 the discovery—through private recordings of course!—of sexual impropriety in The White House would be used as a mercenary tool for anyone and everyone’s personal ends?

The personal had become the political had become the personal had become the political had become the personal and back and forth again until it had all become twisted and consumed like a pretzel. This essay is not here to untangle Bill Clinton’s sexual conduct and misconducts—to do so would require a whole new essay—but merely to suggest that the story of Monica Lewinsky, and Kenneth Starr, and the blue dress, and Linda Tripp, and a particularly placed cigar, is the defining story of the Clinton years.

When I call the Lewinsky affair the defining story Clinton of the years, I do not mean that it is the most important story the Clinton years—look at today’s mass incarceration statistics, police militarization, high rates of home-grown domestic terror, or bottoming out of the middle and working-class, for a glimpse at what was lurking the whole time in that ignored parallel universe known as reality—when I call the Lewinsky affair the defining story Clinton of the years, I simply mean that no event defined the forces of media distraction and self-interest better than this event.

As Don DeLillo once wrote, “reality doesn't happen until you analyze the dots.” Here is the trick we learned in the nineties, if you disperse the dots into the ether of no context—the spin doctors on television, the ramblings of radio hosts, the reams of web text—then the dots can never be connected and the fantasy world can remain. The Gulf War did not take place! I’m not Black; I’m OJ! If the glove doesn’t fit, you must acquit! I do not recall! I did not have sexual relations with that woman! Read my lips, no new taxes! In the words of Oprah Winfrey—the decade’s patron saint of self-actualization—“you become what you believe.”

“He'd lost track of what he wanted, and since who a person was, was what a person wanted, you could say that he'd lost track of himself.”—The Corrections (2001)

In his 1997 novel Underworld, Don DeLillo wrote that “longing on a large scale is what makes history,” but what happens if you eliminate longing? What happens if contradiction and conflict are replaced by maintenance of the status quo? If you can end longing then maybe you can end history. There is nothing left to envision. There is nothing left to change.

“We've come to the end of the road, still I can't let go. It's unnatural” Boyz II Men sang on every radio station in America.

“Well it's over, I know it but I can't let go” Lucinda Williams sang onto the Walkmans of Americans who would never listen to Boyz II Men.

Long before DeLillo published his 1997 novel, there was another much older story about The Underworld. This was the story of Tantalus, a man punished by Hades to stand in a river that dried up the moment he tried to drink water and to stand beside a tree that withered away every time he tried to grab fruit to eat. The punishment lasts an eternity, and so for an eternity Tanatalus tries and fails to find relief. You could argue that this Greek myth was just as relevant to the Clinton years as the writings of DeLillo. The single-minded attempt to satisfy a thirst that can never be quenched? That was happiness in the nineties.

As a 1992 Sprite commercial once commanded, give your brain a rest; obey your thirst!

As the 20th century came to close, The Backstreet Boys released their blockbuster record Millennium. It was the best-selling album of 1999 and one of the Record Industry’s last victory laps before Napster and streaming sent the industry into a permanent death-spiral. In the album’s opening-single, The Backstreet Boys paid their fans the ultimate compliment. “All you people can't you see, can't you see, how your love's affecting our reality? Every time we're down, you can make it right. And that makes you larger than life!”

Now there is your longing on a large scale! The consumer as a force of change! The consumer as a force of power! Sure, the Clinton years didn’t have protests, or paradigm shifts, or any revolutionary change, but those people at the Backstreet Boys concerts—those teenagers lining up in front of the TRL studio sporting cargo shorts and tube tops, those teenagers lining up in front movie theaters clutching light-sabers and Darth Maul masks—those people mattered! This is where the action was happening, through the forces of the market economy. This role as a consumer, this is where you can wield your fantasies of control! Well, Bill Clinton did win the presidency in 1992 with the slogan “It’s the economy, stupid!”

“You can't make history all the time,” James Ellroy wrote in 1995—in one of his Underworld USA Trilogy novels—“sometimes the best you can do is make money.”

Back in the eighties, Americans were obsessed with the idea of subliminal marketing. Behind the national obsession with consumption and spending, lurked a sneaking suspicion that freedom of choice was a lie. There had to be someone pulling the levers. Congress held hearings over the issue. In 1990, Judas Priest was sued on the allegations that their music was covertly encouraging fans to commit suicide. Bandleader Rob Halford dismissed the idea that the music contained any deeper meaning. As Halford explained, if his band, Judas Priest, had really wanted to send a subliminal message, that message would have been “Buy more of our records.”

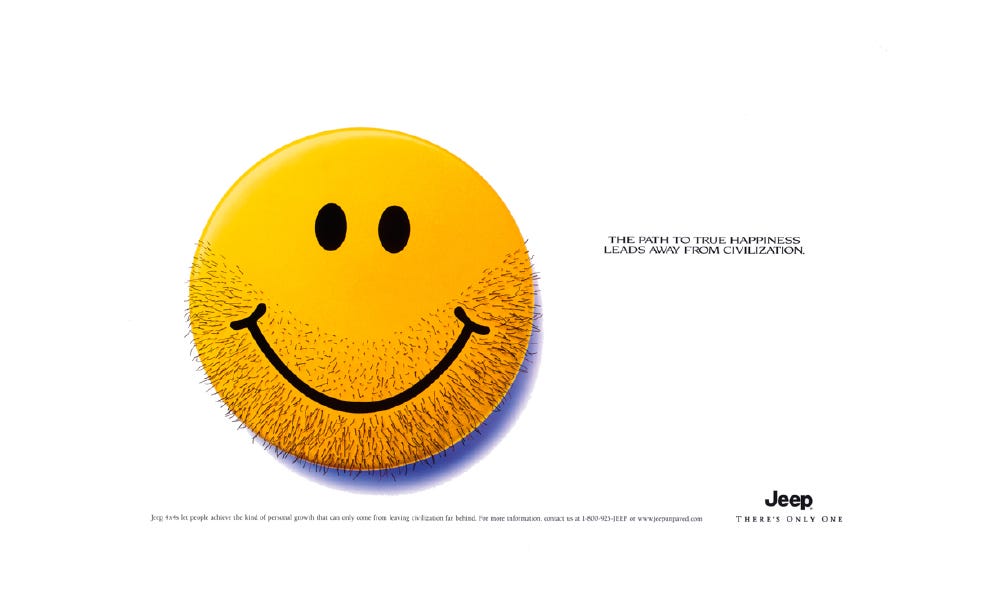

There wasn’t a lot of subtlety in the nineties. Every advertisement was a command. Every movie was a message. Every depiction of emotions was underscored by the swell of orchestra strings and dramatic vocals. Text was merging with subtext. There were still too many dots to connect, but if you just focused on the giant dots the companies flashed before you, it didn’t really matter. As Ellen Willis wrote, “Don’t Think, Smile!”

There was a lot of irony in nineties, but irony isn’t subtlety. Irony is an escape from subtlety. Irony is an escape from meaning. Irony is abnegation to incoherence. Irony is faking the upper-hand by stepping away from the whole mess. Irony is preemptively ceding control.

No song understood the compression of imagination during the Clinton years better than the song “Flagpole Sitta” by Harvey Danger. “Flagpole Sitta” is a song that acknowledges “the tension between being both a cultural observer and a participant—when you’re self-aware enough to notice how the underground is being co-opted, but yet simultaneously caught up in (and horrified by) this commodification.”

The best moment in “Flagpole Sitta” occurs during the bridge when the band details the personal, meaningless acts of self-branding that have become the counterculture’s new stand-in for rebellion.

I wanna publish 'zines

And rage against machines

I wanna pierce my tongue

It doesn't hurt, it feels fine!

The trivial sublime

And that was where we were as the 20th century came to a close. The voices of dissent had turned inward and away from anything that mattered. Alternative culture—in the words of Harvey Danger’s drummer Evan Sult—was at an “ironic remove […] yearning to be part of something, but not being able to get around the suspicion and the self-loathing.” The future belonged to the earnest advocates of mass culture and the capitalists who propped up their fantasies.

“What haunts me,” Naomi Klein wrote in 1999, “is not exactly the absence of literal space so much as a deep craving for metaphorical space: release, escape, some kind of open-ended freedom.”

“Give me coffee and TV” Graham Coxon sang in 1999, “History—I've seen so much, I'm going blind. I'm brain-dead virtually.”

In 1997, Bill Clinton told Americans, “Our land of new promise will be a nation that meets its obligations, a nation that balances its budget”

In 1997, Thom Yorke sang “I'll take a quiet life, a handshake of carbon monoxide”

In 1997, Don DeLillo wrote, “I long for the days of disorder”

In 1997, Sheryl Crow sang “If it makes you happy, then why the hell are you so sad?”

“Pain is just another form of information.” That’s also a quote by DeLillo.

In the nineties, our brains became computers, and all our feelings could be fixed if our neural networks were stimulated correctly. That’s the funny thing about us humans, we have enough imagination to create new technology, but not enough imagination to envision ourselves as making sense outside of the parameters of whatever newest technology we’ve created.

“I feel like a defective model” Elizabeth Wurtzel wrote in her decade defining memoir Prozac Nation, “like I came off the assembly line flat-out fucked and my parents should have taken me back for repairs before the warranty ran out.”

Dr. Melfi: With today's pharmacology, no one needs to suffer feelings of exhaustion and depression.

Tony Soprano: Here we go. Here comes the Prozac.

If the hardware and wiring of your brain was malfunctioning in nineties—or if in the words of a hit Third Eye Blind song, you just wanted something else to get you through this semi-charmed kind of life—you were in luck. The Clinton years ushered in the pharmaceutical market as a buyer’s paradise. Prozac became wildly available in 1987, permanently ushering in the existence of safer, milder antidepressants. By the time Wurtzel published Prozac Nation, in 1994, the memoir’s specific brand of medication had established itself in the mainstream lexicon. The same went for stimulants like Ritalin—legal speed—a medication that, along with the accompanying diagnosis ADHD, experienced massive growth and normalization in the nineties.

[It is here where I acknowledge that I am currently writing this essay while on my daily psychiatrist prescribed dosage of Adderall and Prozac.]

This was the fantasy of the Clinton years, that the magic of modern science would eliminate all pain, suffering, and unproductive distraction. In this brave new world of technology we would be, in the words of Radiohead, “fitter, happier, more productive, comfortable, not drinking too much, getting regular exercise at the gym three days a week, getting on better with your associate employee contemporaries” and finally “at ease.”

It is undeniable that stimulants and antidepressants have helped people live more bearable lives. It is also undeniable that stimulants and antidepressants come with side-effects. One of the most well-known side-effects is the blunting of desire. Psychiatric medications have a tendency to the dial down the intensity of an individual’s longing on a personal scale.

Let me state it more clearly, antidepressants cause impotence.

Impotent: defined as the inability to take effective action; helpless or powerless

There is, however, good news. If your impotence is having a negative impact on your sex life, 1996 Republican Presidential candidate Bob Dole has a solution in the form of another pharmaceutical drug. Viagra doesn’t correct the non-quantifiable problem of emotional indifference to sex, but it does fix the hardware. You don’t actually have to feel anything to perform correctly.

Speaking of computers, I would remiss if I made a nineties playlist that didn’t feature a few songs about the rise of the internet, or as well all called it back then, The Information Superhighway. Well, okay, I have never used that term, non-ironically, but I’ve been told this a term we once used as shorthand for the internet! (Full disclosure: I’m old enough to remember my family getting their our first boxy PC in 1997—and my mom declaring “I’m not convinced this is going to be the future” as the Microsoft software took an intolerable number hours to load—but I’m young enough that I have no memory of AOL Dial-Up or understanding of A/S/L. I arrived online only in time for memories to begin with the rise of Instant Messenger and Myspace.) For my inclusion of online life I have featured the glorious Britney Spears period piece “E-Mail My Heart” and British acid-jazz pop singer Jamiroquai’s dystopian jam “Virtual Insanity.”

In the 1997 song “Virtual Insanity” Jamoriquai sings “we can always take but never give, and now things are changing for the worse”

In 1998, pop-rock band, The New Radicals, closed out their hit songs “You Get What You Give” by listing a litany of late nineties anxieties “Health Insurance: rip-off, lying, FDA: big bankers buying, Fake computer crashs, dining, Cloning while they're multiplying” followed by the statement “Fashion shoots with Beck and Hanson, Courtney Love and Marilyn Manson. You're all fakes, run to your mansions. Come around, we'll kick your ass in." The New Radical’s lead singer, Gregg Alexander, later explained that the purpose of these lyrics was to see whether the media would focus more on the political lyrics or the fake celebrity feuds he concocted for the song. The celebrity insults, unsurprisingly, helped provide the song with the bulk of its media attention.

In 1997, big businesses got bigger. “Indirectly,” the Washington Post reported “this puts pressure on money managers and securities analysts to push corporate managers to deliver growth that is far above that which their underlying businesses have been providing. The only way out of this box, for many in such slow-growth industries as banking, insurance and utilities, is to purchase the growth by buying a competitor.

In 1997, world leaders convened Kyoto Japan and promised that, to avert imminent human extinction, industrialized countries would cut their carbon emissions by 5.2% by the year 2012. It is now 2020, and carbon emissions have grown by over 3.1% since that meeting in Kyoto.

“Technology also is driving merger activity,”the Washington Post reported in 1997. “The pace of consolidation is accelerating […] Five years from now, the financial services industry will look nothing like it does today."

“Why not think about times to come, and not about the things that you've done" Lindsay Buckingham sang during a much-heralded 1997 Fleetwood Mac reunion concert. “If your life was bad to you, just think what tomorrow will do.” This was Bill Clinton’s 1992 campaign song.

Don't stop thinking about tomorrow

Don't stop, it'll soon be here

Yesterday's gone, yesterday's gone

There is so much more I’d like to write about the Fools Gold that was the Clinton years. There is so much more I’ll probably write, one day, about the Fools Gold that was the Clinton years. But, for now, I’ll write this: I’ve compiled many playlists that feature hipper, more interesting, and far superior music, but never have I made a playlist that provides me more joy than what I feel every time I listen to these songs, and then inevitably press repeat to listen again and again.

Is that description of the playlist also a metaphor for the nineties? Probably!

I hope this playlist can transport you to that feeling of dislocation and distraction that defined the decade. The pop culture of the nineties was typically one of ephemera—this was the decade that codified the one-hit-wonder as a major pop genre—and therefore much of this playlist is made up of that ephemera. If you want to really understand the nineties you need to stuff yourself with empty pleasure until the sadness finally becomes impossible to ignore. [Sidenote: two works of art that truly understand this dynamic are Ezra Edelman’s fantastic ESPN documentary OJ: Made In America and also the 1994 finale to the ABC sitcom Dinosaurs…] Not every bubbly pop song on this playlist is a covert critique of nineties consumption, but, I’ve discovered that a surprising number of nineties one-hit-wonders benefit from actually listening to the lyrics.

Alright, finally here is the moment I present my Magnum Opus, a Spotify playlist about Bill Clinton! I hope you enjoy the music, and for those of you who came of age in the nineties, may this bring back fond memories. It was too good to be true. I hope you had the time of your life.

Tracklist

Mambo No. 5 (A Little Bit Of…) by Lou Bega

Every Morning by Sugar Ray

Gettin’ Jiggy Wit It by Will Smith

No Rain by Blind Melon

Too Good To Be True by Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers

All I Wanna Do by Sheryl Crow

Walkin’ On The Sun by Smash Mouth

The Sign by Ace of Base

E-Mail My Heart by Britney Spears

Virtual Insanity by Jamiroquai

Fitter Happier by Radiohead

Semi-Charmed Life by Third Eye Blind

Flagpole Sitta by Harvey Danger

Steal My Sunshine by Len

Hand in my Pocket by Alanis Morisette

If It Makes You Happy by Sheryl Crow

Who Will Save Your Soul by Jewel

Coffee and TV by Blur

Mo Money Mo Problems by Notorious B.I.G. (feat. Puff Daddy)

Tubthumping by Chumbawumba

MMMbop by Hanson

You Get What You Give by New Radicals

Don’t Stop—Live at Warner Brothers Studio by Fleetwood Mac

Good Riddance (Time of Your Life) by Green Day

—Katherine